Why good teaching helps you do better research

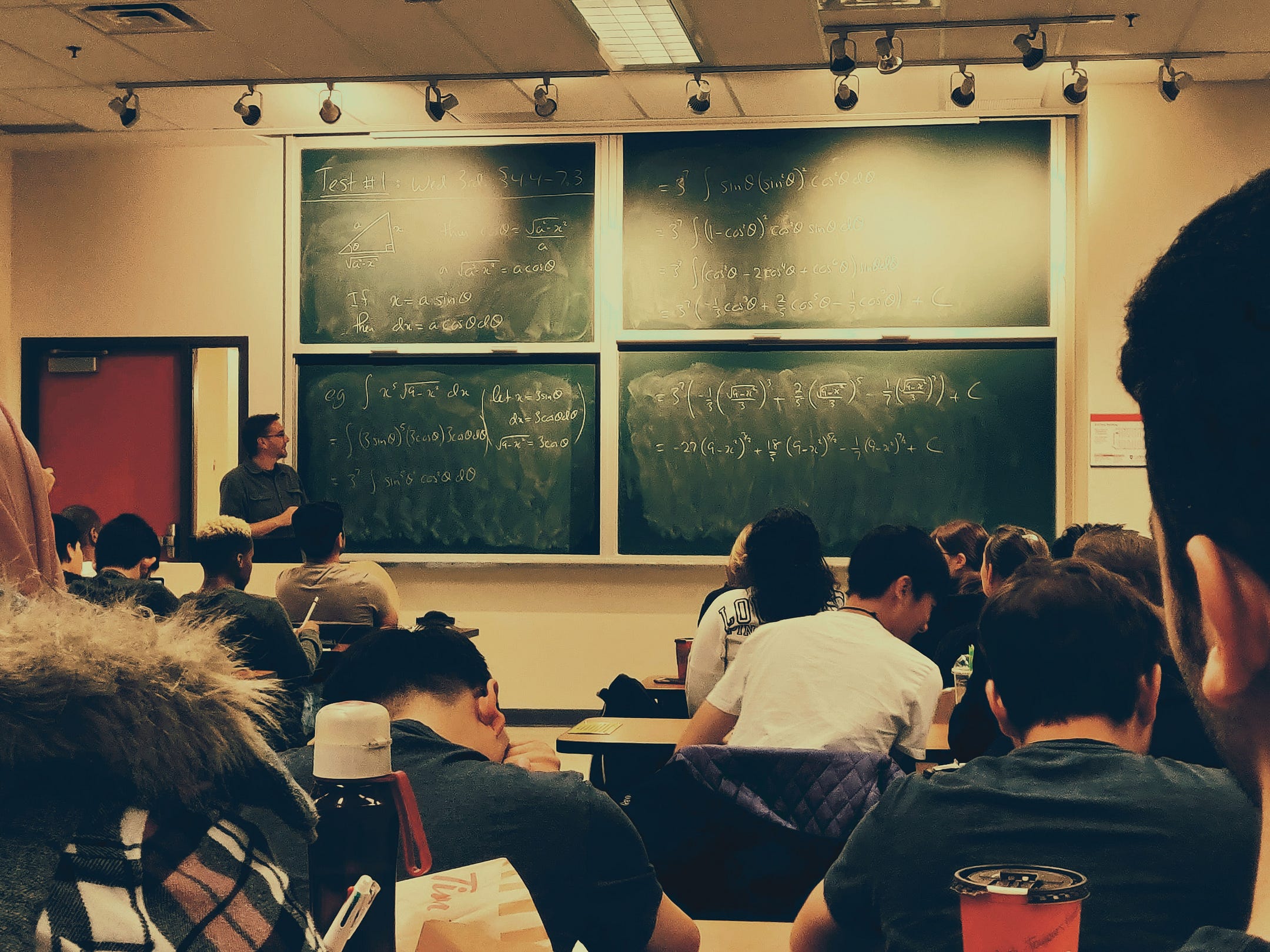

Photo by Shubham Sharan on Unsplash

Photo by Shubham Sharan on Unsplash

In this blog post, I would like to discuss academic teaching with you; Why teaching is frowned upon by many researchers, and how it can actually help them be better at doing research by teaching great courses.

Part 1: The dilemma of teaching

Researchers at institutions with teaching assignments often find themselves faced with a dilemma when it comes to teaching: How can they spend precious time teaching that brings them no immediate benefit that would help them with their career (writing academic papers and getting funding)? Don’t get me wrong here; I assume many professors and other teaching staff know perfectly well that teaching is one of if not the most important duties of any university. It serves as a sacred haven of knowledge where the half-gods of science descent into the earthly realms and bless the students with their knowledge and wisdom. Leaving biblical metaphors aside, we can also clear why so many professors frown upon the teaching responsibilities they have, and most probably wish they could assign this responsibility to someone else (which they sometimes do). But how blame them? It is true that not many incentives exist for teaching staff to spend more time on teaching, or — more importantly — do better teaching. Sure, some universities honor great lectures crafted with skill and foresight by highly motivated and talented teaching staff, with teaching prizes, but this is clearly the minority and I argue that most of these great teachers would have done so even without the prices — they are simply motivated by their own account.

It is a curious fact that professors stand in front of hundreds of young students and try to shovel knowledge into their heads while typically having absolutely no formal qualification for doing so.

They are good at publishing papers and collecting funds, otherwise, they would probably not have gotten that position, but they don’t know how to explain their research field to newcomers. While school teachers spend many years of their training honing their didactics skills and practicing in actual classes, teaching staff at universities mostly study the academic content they are later expected to digest and pass on to their students. That being said, I am wondering how academia can motivate researchers to do better teaching by directly rewarding good teaching? Could “teaching credits” be directly converted to citations, the most important external measurement of success of a researcher? Or even converted to direct funding? I am uncertain if such measures actually help to alleviate the problem of unmotivated and bad teaching at universities. Maybe students should not expect good teaching after all since they should be able to learn concepts without pre-digestion by a teacher anyway? Regardless of what the ideal teaching concepts in academia might look like, I am trying to make the point that making an effort to make good and inspiring lectures can actually help lecturers with their own academic career regardless of extrinsic motivation by the academic system.

Part 2: How teaching can help to be a better researcher

In part 1, we discussed the deficiencies of today’s academic institutions when it comes to teaching obligations. It is true that there is no obvious path out of this situation and changes will come slowly, as always in academia. However, if you are a teaching researcher, I would like to point you towards possible novel views that you can apply today which might help you to do a better job at teaching.

- Teaching can bring you new ideas that you had not before: Technical discussions with bright students can be very fruitful both for teachers and students. Every student brings a different background to the table and provides personal insight into the problem. While most questions by students might not cause immediate new ideas, we all know the “Mh… I have never thought of it like that before”-feeling that sometimes leads to a new way of investigating a problem.

- If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough. This famous Einstein quote, in a nutshell, can serve as a pretty good rule of thumb for differentiating between teachers and great teachers. If you are not able to break a concept down to its core ideas, you know that you deeply understood the concept. Applying this rule to yourself as a teacher can help you detecting deficiencies in your own understanding of the subject that you might otherwise have missed. True experts in their field and great teachers can explain a concept at multiple levels of prior knowledge while still being concise. They have truly mastered their field. For example, take a look at the following video:

- Teaching is a unique and fun experience. Teaching can be rewarding in its own way if you are the type for it. Standing in front of a class can be fun if you have motivated and bright students willing to delve into technical discussions with you.

- Teaching helps to repeat the essentials: There is a reason why you talk about topic X in your lectures, right? Every student in your course should be able to explain this topic to their colleagues after taking your course. And so should you be. Teaching helps to repeat the essentials of your subject in-depth which you might otherwise have forgotten.

- Good teaching draws talent. In my personal view, this is the most important aspect of doing great teaching. If you are able to give insightful lectures you will note an increase in applications for graduate and post-graduate students. Your lecture serves as one of the most important advertisements for your academic chair — one of the few opportunities for students to know what you are actually doing. It is important to remember that if you cannot recruit great talent, your chair will not be able to hold to its current standards once all the current graduates have left. Which will directly affect the quality of your research and your academic output in the long run.

Last but not least, I will leave you with the following beautiful quote by infamous Richard Feynman who has an inspiring story to tell about teaching in Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!

I don’t believe I can really do without teaching. The reason is, I have to have something so that when I don’t have any ideas and I’m not getting anywhere I can say to myself, “At least I’m living; at least I’m doing something; I am making some contribution” — it’s just psychological. When I was at Princeton in the 1940s I could see what happened to those great minds at the Institute for Advanced Study, who had been specially selected for their tremendous brains and were now given this opportunity to sit in this lovely house by the woods there, with no classes to teach, with no obligations whatsoever. These poor bastards could now sit and think clearly all by themselves, OK? So they don’t get any ideas for a while: They have every opportunity to do something, and they are not getting any ideas. I believe that in a situation like this a kind of guilt or depression worms inside of you, and you begin to worry about not getting any ideas. And nothing happens. Still no ideas come. Nothing happens because there’s not enough real activity and challenge: You’re not in contact with the experimental guys. You don’t have to think how to answer questions from the students. Nothing! In any thinking process there are moments when everything is going good and you’ve got wonderful ideas. Teaching is an interruption, and so it’s the greatest pain in the neck in the world. And then there are the longer period of time when not much is coming to you. You’re not getting any ideas, and if you’re doing nothing at all, it drives you nuts! You can’t even say “I’m teaching my class.”

Thank you for reading! Let me know in the comments how you feel about teaching if you are a researcher yourself, or your perception of teaching staff if you are a student!