Self-Supervised Visual Terrain Classification

In this post, I present a summary of my findings from my most recent paper Self-Supervised Visual Terrain Classification from Unsupervised Acoustic Feature Learning. A preprint is available here and the project website is available at http://deepterrain.cs.uni-freiburg.de/.

This post is more technical than my usual posts. If you have any questions about the research, please post questions in the comments. Thanks!

Introduction

Recent advances in robotics and machine learning have enabled the deployment of autonomous robots in challenging outdoor environments for complex tasks such as autonomous driving, last-mile delivery, and patrolling. Robots operating in these environments encounter a wide range of terrains from paved roads and cobblestones to unstructured dirt roads and grass. It is essential for them to be able to reliably classify and characterize these terrains for safe and efficient navigation. This is an extremely challenging problem as the visual appearance of outdoor terrain drastically changes over the course of days and seasons, with variations in lighting due to weather, precipitation, artificial light sources, dirt or snow on the ground. Therefore, robots should be able to actively perceive the terrains and adapt their navigation strategy as solely relying on pre-existing maps is insufficient.

Most state-of-the-art learning methods require a significant amount of data samples which are often arduous to obtain in supervised learning settings where labels have to be manually assigned to data samples. Moreover, these models tend to degrade in performance once presented with data sampled from a distribution that is not present in the training data. In order to perform well on data from a new distribution, they have to be retrained after repeated manual labeling which in general is unsustainable for the widespread deployment of robots. Self-supervised learning allows the training data to be labeled automatically by exploiting the correlations between different input signals thereby reducing the amount of manual labeling work by a large margin.

Furthermore, unsupervised audio classification eliminates the need to manually label audio samples. We take a step towards lifelong learning for visual terrain classification by leveraging the fact that the distribution of terrain sounds does not depend on the visual appearance of the terrain. This enables us to employ our trained audio terrain classification model in previously unseen visual perceptual conditions to automatically label patches of terrain in images, in a completely self-supervised manner. The visual classification model can then be fine-tuned on the new training samples by leveraging transfer learning to adapt to the new appearance conditions.

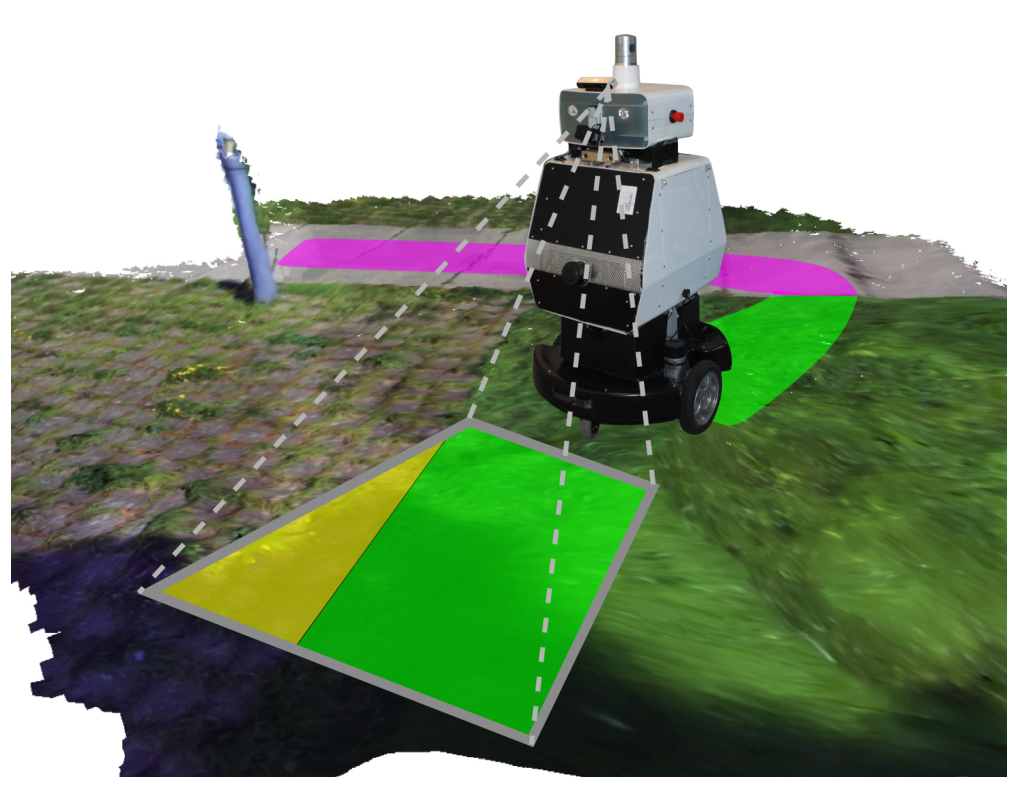

Fig. 1: Our self-supervised approach enables a robot to classify urban terrains without any manual labeling using an on-board camera and a microphone. Our proposed unsupervised audio classifier automatically labels visual terrain patches by projecting the traversed tracks into camera images. The resulting sparsely labeled images are used to train a semantic segmentation network for visually classifying new camera images in a pixel-wise manner.

Fig. 1: Our self-supervised approach enables a robot to classify urban terrains without any manual labeling using an on-board camera and a microphone. Our proposed unsupervised audio classifier automatically labels visual terrain patches by projecting the traversed tracks into camera images. The resulting sparsely labeled images are used to train a semantic segmentation network for visually classifying new camera images in a pixel-wise manner.

In our work, we present a novel self-supervised approach to visual terrain classification by exploiting the supervisory signal from an unsupervised proprioceptive terrain classifier utilizing vehicle-terrain interaction sounds. Fig. 1 illustrates our approach where our robot equipped with a camera and a microphone traverses different terrains and captures both sensor streams along its trajectory. The poses of the robot recorded along the trajectory enables us to associate the visual features of a patch of ground that is in front of the robot initially with its corresponding auditory features when that patch of ground is traversed by the robot. We split the audio stream into small snippets and embed them into an embedding space using metric learning. To this end, we propose a novel triplet sampling method based on the visual features of the respective terrain patches. This now enables the usage of triplet loss formulations for metric learning without requiring ground truth labels. We obtained the aforementioned visual features from an off-the-shelf image classification model pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset. To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to exploit embeddings from one modality to form triplets for learning an embedding space for samples from an extremely different modality. We interpret the resulting clusters formed by the audio embeddings as labels for training a weakly-supervised visual semantic terrain segmentation model. We then employ this model for pixel-wise classification of terrain that is in front of the robot and use this information to build semantic terrain maps of the robot environment.

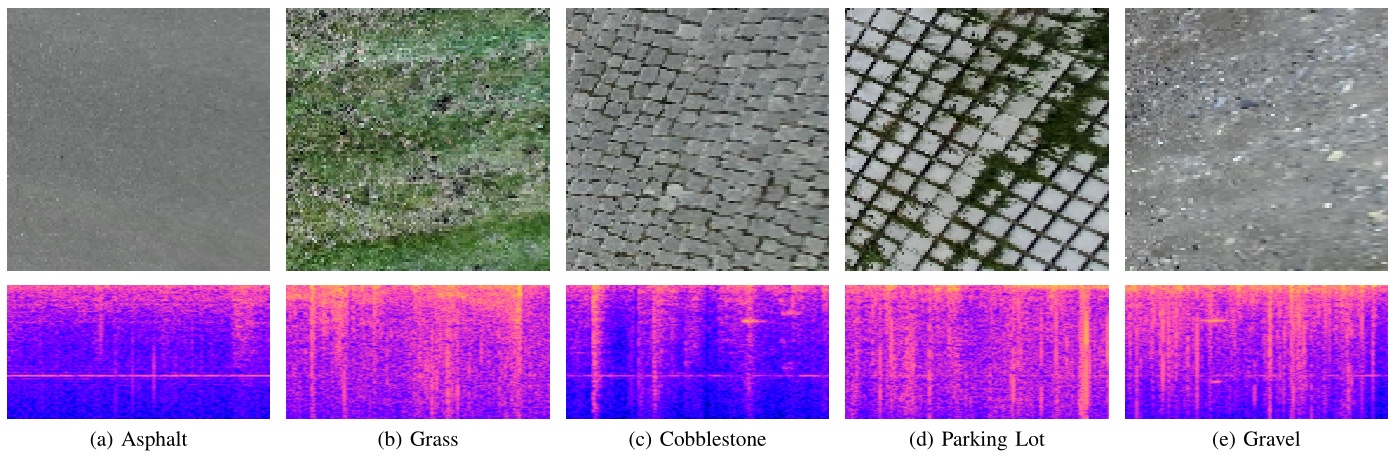

Fig. 2: The five terrain types along with a birds-eye-view image and the corresponding spectrogram of the vehicle-terrain interaction sound from the five different terrain classes

Fig. 2: The five terrain types along with a birds-eye-view image and the corresponding spectrogram of the vehicle-terrain interaction sound from the five different terrain classes

Technical Approach

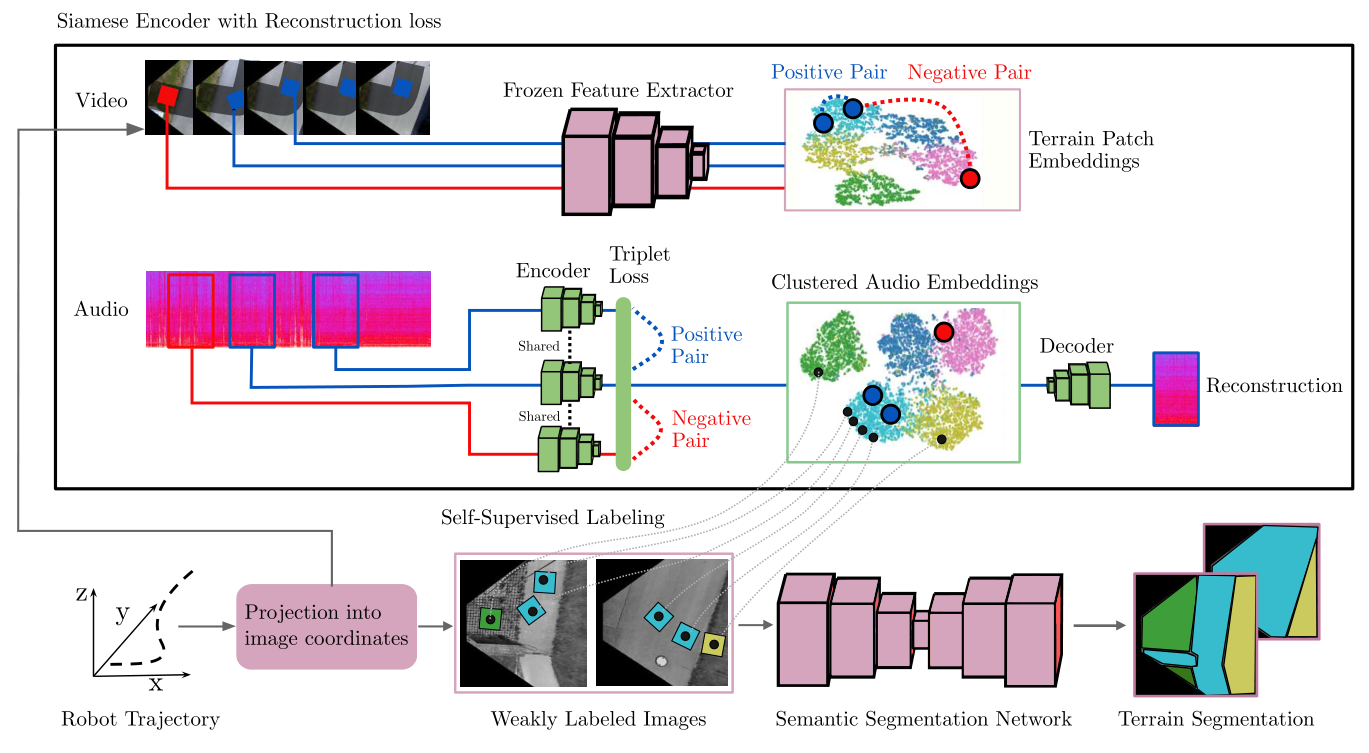

In this section, we detail our proposed self-supervised terrain classification framework. Fig. 3 visualizes the overall information flow in our system. While acquiring the images and audio data, we tag each sample with the robot pose obtained using our SLAM system. We then project the camera images into a birds-eye-view perspective and project the path traversed by the robot in terms of its footprint into this viewpoint. We transform the audio clips into a spectrogram representation and embed them into an embedding space using our proposed Siamese Encoder with Reconstruction loss on audio triplets that uses features in the visual domain for triplet forming. Subsequently, we cluster the embeddings and use the cluster indices to automatically label the corresponding robot path segments in the birds-eye-view images. The resulting labeled images serve as weakly labeled training data for the semantic segmentation network. Note that the entire approach is executed completely in an unsupervised manner. The cluster indices can be used to indicate terrain labels such as Asphalt and Grass or in terms of terrain properties.

Fig. 3: Overview of our proposed self-supervised terrain classification framework. The upper part of the figure illustrates our novel Siamese Encoder with Reconstruction loss (SE-R), while the lower part illustrates how the labels obtained from the SE-R are used to automatically annotate data for training the semantic segmentation network. The camera images are first projected into a birds-eye-view perspective of the scene and the trajectory of the robot is projected into this viewpoint. In our SE-R approach, using both the audio clips from the recorded terrain traversal and the corresponding patches of terrain recorded with a camera, we embed each clip of the audio stream into an embedding space that is highly discriminative in terms of the underlying terrain class. This is performed by forming triplets of audio samples using the visual similarity of the corresponding patches of ground obtained with a pre-trained feature extractor. We then cluster the resulting audio embeddings and use the cluster indices as labels for self-supervised labeling. The resulting labeled images serve as a weakly labeled training dataset for a semantic segmentation network for pixel-wise terrain classification.

Fig. 3: Overview of our proposed self-supervised terrain classification framework. The upper part of the figure illustrates our novel Siamese Encoder with Reconstruction loss (SE-R), while the lower part illustrates how the labels obtained from the SE-R are used to automatically annotate data for training the semantic segmentation network. The camera images are first projected into a birds-eye-view perspective of the scene and the trajectory of the robot is projected into this viewpoint. In our SE-R approach, using both the audio clips from the recorded terrain traversal and the corresponding patches of terrain recorded with a camera, we embed each clip of the audio stream into an embedding space that is highly discriminative in terms of the underlying terrain class. This is performed by forming triplets of audio samples using the visual similarity of the corresponding patches of ground obtained with a pre-trained feature extractor. We then cluster the resulting audio embeddings and use the cluster indices as labels for self-supervised labeling. The resulting labeled images serve as a weakly labeled training dataset for a semantic segmentation network for pixel-wise terrain classification.

We will now briefly discuss the major steps in the processing pipeline.

Trajectory Projection Into Image Coordinates

We record the stream of monocular camera images from an on-board camera and the corresponding audio stream of the vehicle-terrain interaction sounds from a microphone mounted near the wheel of our robot. We project the robot trajectory into the image coordinates using the robot poses obtained using our SLAM system. We additionally perform perspective warping of the camera images in order to obtain a birds-eye view representation.

Unsupervised Acoustic Feature Learning

Each terrain patch that the robot traverses is represented by two modalities: sound **and **vision. We obtain the visual representation of a terrain patch from a distance using an on-board camera, while we record the vehicle-terrain interaction sounds by traversing the corresponding terrain patch. For our unsupervised acoustic feature learning approach, we exploit the highly discriminative visual embeddings of terrain patch images obtained using a CNN pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset to form triplets of audio samples. To form such discriminative clusters of embeddings, triplet losses have been proposed. We argue that the relative position of a terrain patch image embeddings in embedding space serves as a good approximation for ground truth labels that have previously been relied on for triplet forming. We form triplets of audio clips using this heuristic. Finally, we train our Siamese Encoder with reconstruction loss in order to embed these audio clips into a highly discriminative audio embedding space.

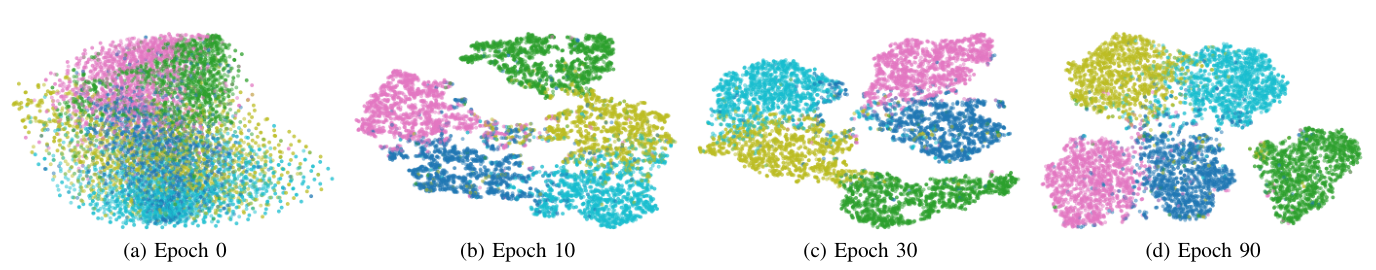

Fig. 4: Two-dimensional t-SNE visualizations of the audio samples embedded with our SE-R approach after 0, 10, 30, and 90 epochs of training. The color of the points indicate the corresponding ground truth class. We observe that clusters of embeddings are clearly separable as the training progresses and they highly correlate with the ground truth terrain class.

Fig. 4: Two-dimensional t-SNE visualizations of the audio samples embedded with our SE-R approach after 0, 10, 30, and 90 epochs of training. The color of the points indicate the corresponding ground truth class. We observe that clusters of embeddings are clearly separable as the training progresses and they highly correlate with the ground truth terrain class.

The triplet loss enforces that the embeddings of samples with the same label are pulled together in embedding space and embeddings of samples with different labels are pushed away from each other simultaneously. As the ground truth labels of the audio samples are not available to form triplets, we argue that an unsupervised heuristic can serve as a substitute signal for the ground truth labels for triplet creation: the local neighborhood of the terrain image patch embeddings. We obtain rectangular patches of terrain by selecting segments of pixels along the robot path. The closest neighbor in the embedding space has a high likelihood of belonging to the same ground truth class as the anchor sample. Therefore, for sampling triplets, we select the sample with the smallest euclidean distance in the visual embedding space as a positive sample. We then select negative samples by randomly selecting samples that are in a different cluster in visual embedding space than the anchor sample. Although it cannot be always guaranteed that the negative sample does not have the same ground truth class, it has a high likelihood of belonging to a different class, which we observe in our experiments. Likewise, we argue that visually similar terrain patches have a high likelihood of belonging to the same class. This means that in practice a fraction of the generated triplets are not correctly formed. However, we empirically find that it is sufficient if the majority all triplets have correct class assignments as they outweigh the incorrectly defined triplets.

Finally, we perform k-means clustering of the embeddings to separate the samples into K clusters, corresponding to the K terrain classes present in the dataset. Our approach only requires us to set the number of terrain classes that are present and assign terrain class names to the cluster indices.

Self-Supervised Visual Terrain Classification

We use the resulting weakly self-labeled birds-eye-view scenes to train a semantic segmentation network in a self- supervised manner. A self-supervisory signal can be obtained for every image pixel that contains a part of the robot path for which the label is known from the unsupervised audio clustering. Note that the segmentation masks for the traversed terrain types are incomplete as the robot cannot be expected to traverse every physical location of terrain in the view to generate complete segmentation masks. We alleviate this challenge by considering all the pixels in camera images that do not contain the robot path as a background class that does not contribute to the segmentation loss. We deal with the class imbalance in the training set by weighing each class proportional to its log frequency in the training data set.

Results

We will briefly discuss some of the results reported in the original publication.

Qualitative Results

Fig. 6 illustrates some qualitative terrain classification results for a small clip in the dataset. We observe that a majority of pixels in each frame are assigned the correct labels. Some errors occur for terrains that are partially covered with objects (bikes in this scene) or have non-favorable lighting conditions.

Fig. 6: Qualitative terrain classification results for a small clip in the dataset.

Fig. 6: Qualitative terrain classification results for a small clip in the dataset.

For more qualitative and quantitative results, please refer to the original publication.

Generalization to Terrain Appearance Changes

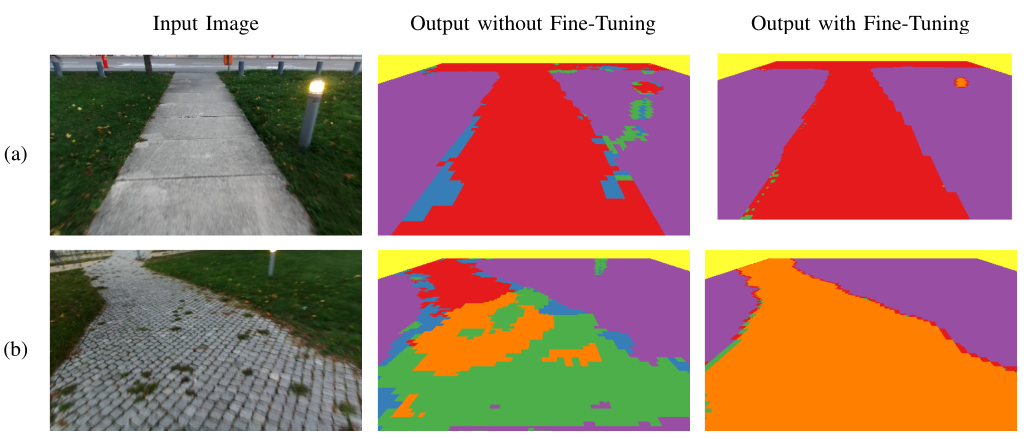

One of the major advantages of our self-supervised approach is that new labels on previously unseen terrains can easily be generated by the robot automatically. While the terrain traversal sounds do not substantially vary with the weather conditions other than rain and winds, the visual appearance of terrain can vary depending on several factors including time of day, season or cloudiness. We record data at dusk with low light conditions and artificial lighting resulting in a variation in terrain hues and substantial motion blur. We qualitatively compare the terrain classification results for a model trained exclusively on the Freiburg Terrains dataset and a model trained jointly on the Freiburg Terrains dataset as well as on the new low light dataset. Qualitative results from this experiment are shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7: Qualitative results on a new low light dataset that was captured at dusk that has a considerable amount of motion blur, color noise, and artificial lighting. We show a comparison between the terrain classification model without and with fine-tuning on training data created using our self-supervised approach.

Fig. 7: Qualitative results on a new low light dataset that was captured at dusk that has a considerable amount of motion blur, color noise, and artificial lighting. We show a comparison between the terrain classification model without and with fine-tuning on training data created using our self-supervised approach.

Semantic Terrain Mapping

We finally demonstrate the utility of our proposed self-supervised semantic segmentation framework for building semantic terrain maps of the environment. To build such a map, we use the poses of the robot that we obtain using our SLAM system and the terrain predictions of the birds-eye-view camera images. We project each image into the correct location in a global map using the 3-D camera pose and we use no additional image blending or image alignment optimization. For each single birds-eye-view image, we generate pixel-wise terrain classification predictions using our self-supervised semantic segmentation model. We then project these segmentation mask predictions into their corresponding locations in the global semantic terrain map, similar to the procedure that we employ for the birds-eye-view images. When there are predictions of a terrain location from multiple views, we choose the class with the highest prediction count for each pixel in the map. We also experimented with fusing the predictions from multiple views using Bayesian fusion which yields similar results. Fig. 8 shows how a semantic terrain map can be built from single camera images and the corresponding semantic terrain predictions of our approach. It can be observed that our self- supervised terrain segmentation model yields predictions that are for the most part globally consistent.

Fig. 8: Tiled birds-eye-view images and the corresponding semantic terrain maps built from the predictions of our self-supervised semantic terrain segmentation model. We use the SLAM poses of the camera to obtain the 6-D camera poses for each frame.

Fig. 8: Tiled birds-eye-view images and the corresponding semantic terrain maps built from the predictions of our self-supervised semantic terrain segmentation model. We use the SLAM poses of the camera to obtain the 6-D camera poses for each frame.

Conclusion

In this work, we proposed a self-supervised terrain classification framework that exploits the training signal from an unsupervised proprioceptive terrain classifier to learn an exteroceptive classifier for pixel-wise semantic terrain segmentation. We presented a novel heuristic for triplet sampling in metric learning that leverages a complementary modality as opposed to the typical strategy that requires ground truth labels. We employed this proposed heuristic for unsupervised clustering of vehicle-terrain interaction sound embeddings and subsequently used the resulting clusters formed by the audio embeddings for self-supervised labeling of terrain patches in images. We then trained a semantic terrain segmentation network from these weak labels for dense pixel-wise classification of terrains that are in front of the robot.

Thanks for reading!